Research: STRATEGY, STATECRAFT, & TECHNOLOGY,

The Changing Character of War

HOW DO STATES EXERCISE POWER?

Soon after the terrorist attacks on the United States on ‘9/11’ in 2001, it was asserted that warfare had changed, and there was some speculation that, perhaps, ‘war’ itself had been superseded. ‘Conventional’ wars, it seemed, were a thing of the past.[i] The future appeared to be one that would be dominated by acts of terrorism or insurgency. For twenty years, there was a pursuit of terrorists and attempts to stabilise states through direct military intervention, with Western coalition forces adopting counter-insurgency methods. However, by 2014, with Russia’s illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and China’s seizure and fortification of atolls in the South China Sea, state coercion took new forms. When Russia blundered into a renewed invasion of Ukraine again in 2022, expecting the swift fall of Kyiv, just two years after an interstate conflict in the Caucasus, it was clear that state warfare had returned.

From its inception in 2003, the Changing Character of War research team challenged the claims that war was a thing of the past, which was then the prevailing orthodoxy, in rigorous detail. The Centre analysed the drivers of change and the extent to which the nature of war could alter, if at all.

The consensus has been, over the years of our research, that the nature of war (that is, its essence) does not change, despite the existence of new actors, contexts, technologies, drivers, and dynamics.[ii] Yet, SST:CCW has identified some prevailing characteristics of war in the early twenty-first century, not least the evident impact of new technologies. We also recognise there are a great many continuities that must not be overlooked, including the techniques of war, the dynamic and visceral nature of conflict, and the impact of ideas.

We have examined the debates about change that have dominated the study of armed conflict in recent decades, including ‘new wars’, ‘law-fare’; the implications of automated systems, cyber and information warfare; the development of AI, and ‘hybrid’ or ‘grey-zone’ warfare. Each of these developments challenge the efficacy of existing strategic, operational, and tactical approaches to warfare: they demand not just technological and capability enhancements, but more comprehensive organisational changes, new initiatives in professional military education, fresh thinking on procurement and supply chains, and strategic leadership.

The profound change wrought by Russia’s war against Ukraine and China’s growing confrontation with the United States, and thus the return of coercion between major states, has been accompanied by the rapid development of specific technologies, from hypersonics and militarised space platforms, through autonomous systems, to the use of the electromagnetic spectrum and the development of artificial intelligence. It is this transformation which has prompted a rethink of the old CCW model of research. In short, it needed a radical new approach, more orientated towards strategy, statecraft, science, and technology. Moreover, it was clear that governments needed the insights and support of university thinkers, agile innovators, and new tech specialists.

In this sense, our research at SST:CCW is not a purely academic endeavour. Our research has a direct impact on how one thinks about armed conflict, its frames of reference, and the intellectual architecture for dealing with future challenges. SST:CCW engages with those in government and practice as a ‘critical agent’, examining change, its implications, and its costs. Nevertheless, we do not simply mirror the anxieties of governments. We seek originality, conduct deep rsearch, and apply rigour.

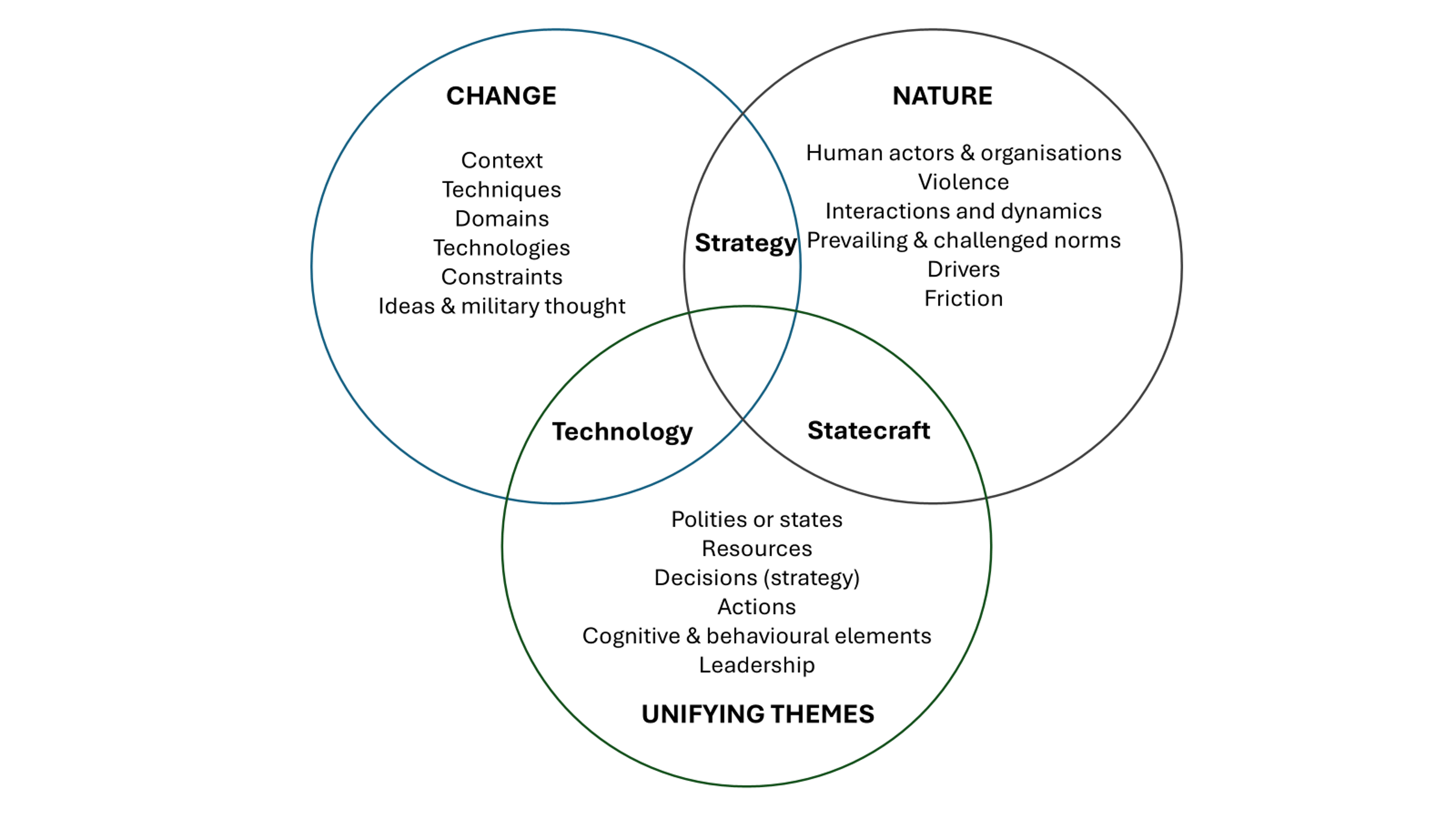

SST:CCW is concerned with the exercise of state power, the direction and leadership of that power, and the impact of these on war or the threat of war. SST:CCW weighs up war potential, conducts net assessments, and identifies themes to analyse change in statecraft and war. The centre cross examines state leadership, foreign policies, and international relations. It studies elements that define war’s unchanging nature, for the purpose of further comparative analysis.

We define statecraft as the exercise of power by states and their leadership. Strategy is decision making and decision execution for the adroit allocation of resources in order to achieve goals. War is a condition of contention by organised armed force, driven by power, on a large scale. Two overarching thematic aspects can be identified in all these elements – the physical and the cognitive, but within each we examine the three areas of change, nature, and continuity.

The six themes of change in war are examined against six elements of the unchanging nature of war, and six areas of continuity. These elements enable us to offer comparisons, measure effect, calibrate the degree of change, and evaluate responses.

THEMES OF CHANGE

1 Context

The context of any armed conflict will be critical to its conduct and its outcome, which is why Carl von Clausewitz regarded the accurate identification of context as the ‘supreme act’ of a statesman.[iii] Miscalculation has often stemmed from a misreading of the purpose or intention of an adversary, a misunderstanding of available resources, and misjudgements over the setting of a conflict in the perspectives of belligerents and neutrals. The context between polities might range between co-operation (as allies or partners), competition, confrontation, coercion (including occupation), and armed conflict (either limited in some form or unlimited). The context may indicate the relative power of belligerents through scale, resources, and relative (dis)advantages.

2 Techniques

The techniques of war range from low level tactics to high or ‘grand’ strategies, as belligerents seek to maximise the effect of their forces and resources to serve their interests and secure an advantage. Techniques are transformed in part by changing circumstances and contexts but also by the advent of new technologies, new adversaries, and asymmetry in conflict. The techniques of successful guerrilla warfare differ greatly from those required in conventional, industrial armed conflict. Different techniques are needed in the context of confrontations between nuclear-armed states. In war in the early twenty-first century, the techniques of war amongst leading states involve the combination of a variety of technologies in surveillance, communications and weaponry, the synchronisation of ‘lines of effort’, the arrangement and sustainment of force, a trade-off between ‘stand-off’ air technologies and close-quarter engagements, and an abundant use of information to garner support or demoralise an adversary. For non-state actors, there is a stronger focus on disruption, attrition, provocation, intimidation, exploitation, and information warfare.[iv]

3 Domains

Armed conflict takes place in a variety of domains, not all of which are physical, but there is a unifying aspect where conflict is actually carried out, which can be considered the operational dimension. The creation of space technologies, primarily for communications and surveillance, has altered the conduct of operations in the air, on land, and by sea. Armed conflicts also occur in peripheral zones that defy conventional military power and ensure protection for stealthy forces, such as congested littorals, vast urban settlements, mountain ranges, and densely vegetated spaces. Nevertheless, the information environment has created proximity and access to global audiences. Electronic connectivity has enabled greater active participation. Various choke points in the world continue to have strategic importance, from the Strait of Hormuz to the Strait of Malacca. Contested territorial claims assert themselves in the relations of states and peoples, including the Taiwan Strait, the Falklands, Kashmir, and the frozen conflicts on Russia’s southern borders. The cognitive space must also be considered, since war is fought in the minds of belligerents and their adherents. Furthermore, the period in which these conflicts take place can be considered as a prevailing phylum or realm, and, paradoxically, this is in constant flux, rendering neat periodisation and thus its assumptions questionable

4 Technologies

Technological developments have an impact on the changing character of war, and greater connectivity through information technology, has created opportunities, advantages, and penalties in stealth, influence, and surveillance. The use and effects of new technologies (including remotely piloted air systems, cyber, artificial intelligence, robotics and automated systems) are much debated, but SST:CCW examines the potential of new technologies when combined together. The most significant challenge identified in the contemporary literature stems from the advent of AI, although assessments are currently too generalised and tend to ignore historical patterns of technological integration. There is coverage of the new information domain and connectivity, and some speculation about the relative power of encryption and decryption enabled by quantum computing. Yet it must be remembered that many previous technological breakthroughs and ‘revolutions’ fell short of expectations. Their impact is often less than antcipated, even if it takes the conduct of warfare into new and unexpected directions.

5 Constraints

Armed conflict may be characterised by intense savagery, but there have been repeated efforts to create codes of conduct, legal restraints, and international instruments to prevent the worst excesses. While atrocities still occur, military institutions have often prided themselves on certain moral virtues. From the mid-nineteenth century there have been conventions, and international agreements, to regularise the treatment of non-combatants, prisoners, and the wounded. The guidance of jus ad bellum has been invoked to justify defence and rightful offence in war, while international humanitarian law has been used to argue for or against armed intervention, even in cases that would otherwise infringe state sovereignty. The law has been used to prosecute soldiers suspected of abuses against civilians (including the use of human shields), although there remain ambiguities concerning insurgents and other violent non-state actors who breach the standards of the Law of Armed Conflict, the Geneva Conventions, and local domestic laws. The notion of ‘high value targeting’, outside of prescribed conflict zones, has raised concerns about their legality and utility. New technologies have also created anxieties about responsibility and accountability, while the prospect of a generation of integrated and independent surveillance-and-weapon systems, which are not dependent on human controls, has magnified such fears. In the nuclear sphere, safeguards, failsafe systems, and protocols (communications, command and control systems) are threatened by proliferation or by cyber penetration, and the efficacy of constraints on the use of all weapons of mass destruction is a pressing matter.

5 Ideas and military thought

The conduct of war, while a pragmatic struggle, has often benefitted from intellectual examination and it is in the realm of ideas that frameworks for assessing change are to be found. Theorists and practitioners have attempted to review techniques, apply scientific ideas, measure effects, assess impacts, and forecast developments. The assessment of past practice, current capabilities and future needs is a constant concern for military professionals and their governments, and it is a matter of survival for non-state actors. At the tactical level, there is a search for the approach that will yield the most rapid and effective results at the lowest cost. At the strategic level, there is a desire for understanding of rivals, particular ‘ways’, and ideas that will sustain populations, allies, and international opinion behind the cause. There are ideas that will maximise the potential of particular technologies, or permit the reform of organisations, or discredit opponents. Attempts to interpret relative strengths, potential, and forecast intentions, or ‘net assessment’, is analysed by SST:CCW. Moreover, we have a keen interest in the intellectual evolution of war, of conflict resolution, and the regulation of conflict.

NATURE OF WAR THEMES

1 Human actors

It was Thucydides who wrote that war was, ultimately, a human concern.[v] As a species, humans have sought protection or the acquisition of critical resources, to satisfy honour and credibility, and to neutralise threats. This required organisation, and a degree of sacralisation, with an understanding of its continued utility over time. Through such mechanisms, violence is transformed to a purposeful human activity, considered worthy of sacrifice. Despite the prevalence of non-state violence, the world’s conflicts are still, to a large extent, decided and determined by state actors. In some cases, states make use of proxies, informal groups of fighters, and sometimes negotiate the control of resources, territory, or conditions. On other occasions, they orchestrate highly organised state forces. Human actors drive conflict, they resolve them, and their behaviours determine success or failure. Our work, and that of our visiting fellows, has covered a wide range of issues concerned with actors, including the strategy of Al-Qaeda and Daesh, the campaign of various groups affiliated to the Taliban of Afghanistan, the US-led Coalition operations in Iraq, the role of the UN, and the targeting of civilians in war. More recently, we have examined the defiance of the Ukrainians against Russian aggression, and the derterioration of Moscow’s war machine. The ‘will to fight’ remains a key component of war. Colonel Ardant du Picq, the French officer who authored Battle Studies in the nineteenth century, once wrote: ‘Technological advances cannot change the human condition and therefore man’s response to combat’.[vi] His injunction was to study the nature of the human in war, as it was the constant feature of conflict.

2 Violence

There are many attempts to illustrate that the nature of war has changed. Throughout history, the introduction of new technologies and techniques has been heralded as transformative. In the Western canon of literature, classical texts identified new weapons and decisive battles as the arbiter of changed nature, while in the modern era the technological and industrial developments pervading economies and societies gave rise to evaluations that emphasised specific weapon systems, transportation, and then powered flight as the forces that changed war’s nature. Perhaps the true claim to a changed nature was the advent of nuclear weapons. In the early twenty-first century, the empowerment of terrorists and insurgents, after five decades of relative stability in a global system of nation states (despite large and prolonged conflicts in Africa, Southeast Asia and the Middle East), led to judgements that war’s nature was irrevocably changed and defined by these actors. Yet, within two decades, this confident assertion was replaced by the notion that electronic communication systems, robotics and artificial intelligence would be so radically different that the essence of war would be determined by them.[vii] Despite these assertions, the fundamentals of war have not changed. There is still a recognisable trinity of government, military, and the people – each with differing reactions to war – and a corresponding trinity of forces.[viii] Crucially, the brutality of collective violence has not changed. War remains a lethal condition, replete with enmity, passion, intensity, the determination to survive, and the desire to assert power over others.

3 Interactions

War is a phenomenon of the human condition, where diversity, developments amongst rivals, changing political objectives, and friction create uncertainties. These produce the dynamics of interaction as belligerents try to gain a relative advantage over their enemies. War has often been regarded as a realm of chance, uncertainty, and of high risk. The reaction of belligerents can be varied too – some respond to a crisis with courage and stoicism, while others give way and ultimately capitulate. The contest of war has been likened to a dual, a boxing match, or a street fight, because it is characterised as a series of blows, of ebbs and flows, sometimes arousing great passions and exertions.[ix] The asymmetry of strengths adds to the unexpected outcomes of the various collisions of war. Thus, the interactive nature of war generates significant challenges for government and military planners, as they try to create contingencies and latitude for rapid change.

4 Prevailing norms

There are commonly held views about what defined each age of warfare. In the 1920s, Basil Liddell-Hart’s advocacy of air and armoured technologies as permanent solutions to the killing fields of the First World War appealed to professional and public audiences eager to avoid the repetition of that costly conflict. After 1945, nuclear weapons created the assumption was that conventional wars were too dangerous to be fought because of escalation risk, and the assumption was that the nature of war was a choice between nuclear annihilation or limited conflict.[x] In the 1990s, Mary Kaldor offered an interpretation of the character of conflict that seemed to satisfy a widespread desire to understand the post-Cold War international order, namely that wars of identity, fought by peoples affected adversely by globalisation, would be the nature of all war in the future.[xi] Contemporaneously with Kaldor, Steven Pinker argued that state-on-state wars, and indeed violence in general, was in terminal decline and the world was becoming more peaceful which appealed to those who had seen the maturing of international institutions.[xii] Peter Singer, among others, captured the popular imagination with his illustration of war fought with cyber, electronic and robotic systems, while Chris Coker argued that, with the rapid development of AI, this may be the last chance that humans have to determine the nature of war.[xiii] Nevertheless, scholars of strategic culture are aware that relics of the past linger on and some characteristics, norms, and ideas are enduring, in part because of political systems, legal regimes, geography, and economic structures. The ways in which particular societies imagine the future of war also tells us a great deal about their present-day concerns and values, rather than any accurate notion of the future itself. Prevailing norms affect not just intellectual interpretations of war, but also the legal regimes that try to regulate and interpret it. Moreover, prevailing norms may set widespread political and societal expectations, and war, when it comes, can be a profound shock.

5 Drivers

War is still driven by fear, honour, interest, survival, uncertainty, bellicose culture, domestic pressure, perceived injustice, reaction to incursion, ambition or opportunism, and error in the form of misunderstanding, misjudgement, or prejudice. It still consists of violence, enmity, passion, chance and friction, rationalised political objectives, dynamic interaction and unpredictability. The problem in the understanding of war today is the desire to portray it as an aberration in international affairs.[xiv] War is seen as exceptional and extreme. The paradox is that it is the invention of peace which is the artificial edifice.[xv] Asserting the normative nature of peace has created significant challenges not only in the pursuit of policy and national defence and security, but also in defining the responsibilities and rights of state power and individual citizenship.[xvi]] This has implications for the conduct of war in an information age and resilience to strategic shocks[xvii]. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, and several conflicts in Africa and the Caucasus in the 2020s indicated that war is still regarded as an instrument of policy, whether legitimate or not.

6 Friction

Chance events and friction have been enduring features of war’s nature. Humans can give way or be incapacitated; technologies can malfunction; there can be sudden adverse weather conditions; or a host of other unexpected developments. In decision-making, friction can assert itself in civil-military disagreements, miscommunication, misreading intelligence, and simple misunderstanding between adversaries.

UNIFYING THEMES

1 Polities or states

The Greek Politeia, the Westphalian state system, and the modern Weberian state have been political structures that conduct war. Even challenges to this organised model of governance, such as non-state actors, are still defined in relation to the state. Despite the variety of forms, from dynastic realms to global empires, the individual and collective actions of states have defined war and differentiated it from terrorism or insurrection.

2 Resources

Quincy Wright, Azar Gat, and Christopher Coker, amongst others, identified the centrality of resources in war.[xviii] For early civilisations, control of critical foodstuffs or minerals was vital for survival, and while waging war. Cicero once astutely observed that ‘the sinews of war are infinite money’. Resources have thus been a cause of war and vital for its sustainment. The exact type has, of course, been dependent on humanity’s stage of technological advancement. Access to water, the ability to trade, the availability of hydrocarbons, control of minerals necessary for industrial or nuclear production, and the manufacturing capacities of micro-processors have been critical at one time or another. Strategies and causal mechanisms have often been predicated on resources, or on ‘means’, and the ability to forecast the relative availability of them.

3 Decisions (strategy)

One of the continuities of war is that humans imagine, plan, and orchestrate their futures, attempting to achieve an advantage through the relative balance of powers offered by resources, geography, determination, allegiance, techniques, technologies, and other elements. Strategy is making decisions and executing them to secure an advantage.[xix] This definition is derived from the original Greek idea of strategoi, the leaders, rather than the modern ideas of ‘battles and campaigning’, a ‘bridge’ between policy and military operations, or ‘creating power’. At the highest level, this can involve the formation of coalitions and alliances, the extraction of vast resources, and the definition of an overarching intention: a grand strategy.[xx] At a smaller scale, the definition of decision remains, but with a more acute focus on one or more of its constituent elements, such as a technique or stratagem. This is one of the central elements of the work of SST:CCW, with publications by its core team members.

4 Actions

War is a condition of practice, not theory. The conduct of war possesses some significant continuities, even where we can acknowledge that every encounter is different. To use the classic philosophical analogy, you cannot step into the same river twice, even though it remains the same river. Military personnel are guided by these continuities, even when faced with novel situations. Some are institutionalised as drills and doctrine, while others are more flexible (‘mission command’). Some are recognised (leading to public decorations, or are identified as conditions of victory or defeat, for example) and others are conditional. The central idea of all actions in war is adaptation, and the calibrated application of resources, to secure an advantage.

5 Cognitive elements

One of the most profound continuities in war is the importance of morale – the willingness to contend, regardless of the conditions. It follows that the ability to access and influence the factors of determination and to shape the physical and informational environment have also been common aspects of war. Forces with distinct advantages have sometimes failed because there was a breakdown in this cognitive element. Equally, forces with odds stacked against them have sometimes produced remarkable successes through this cognitive resilience. It is also recognised that unfamiliar strategic developments will lead leaders to invoke analogies, sometimes inappropriately. In a war going badly, leaders will either suffer doubts or cling to a stubborn faith in a change of fortunes. In the crucible of armed conflict, events forge further distortions of reality.

6 Leadership

Leaders still appear to make a significant difference in armed conflict, and human decision-making remains profound, even where this is enabled by new technologies. The degree to which leaders devolve, either to humans or to machines, is a much-debated area and is dependent on context. SST:CCW plays a role in this discussion and in the shaping of professional military education. The Centre also takes a particular interest in strategic leadership, decision-making, and planning. It has been engaged with assessments of future armed conflict, strategic horizons, and measures of strategic impact, and carries out net assessments to provide more accurate and evidence-based decision-making.

References

[i] Stanford experts: how 9/11 has changed the world (31 August 2011).

[ii] Antulio J. Echevarria II, Clausewitz and Contemporary War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 61–83; Williamson Murray, America and the Future of War: The Past as Prologue (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2017), pp. 34-35; Lt-Gen. H. R. McMaster, “Continuity and Change, The Army Operating Concept and Clear Thinking About Future War,” Military Review (March/April 2015), 5-13.

[iii] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Book I, Chapter 1, Howard and Paret Translation), 100.

[iv] See Robert Johnson, Tim Sweys and Martijn Kitzen, (eds.) The Conduct of War (London: Routledge, 2021); Robert Johnson and Timothy Clack, World Information War (London: Routledge, 2021).

[v] Athanassios G. Platias and Constantinos Koliopoulos, Thucydides on Strategy (Oxford, 2017).

[vi] Ardant du Picq, Battle Studies, 39.

[vii] U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, “The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Future Warfare,” Fort Eustis, VA: U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, (May 2017), 6; Rob Johnson, ‘Predicting Future War’, Parameters, 44, 1 (Spring 2014), 65-76.

[viii] Andreas Herberg-Rothe, ‘Clausewitz’s “Wonderous Trinity” as a Coordinate System of War and Violent Conflict,’ International Journal of Conflict and Violence, Vol. 3, No. 2 2009, 204–219.

[ix] Clausewitz, On War, Book I, Chapter 1, 2., op. cit. See Christopher Coker, Why War? (London: Hurst, 2021), 125.

[x] Lawrence Freedman, Deterrence (London: Polity, 2004), 6-14.

[xi] Mary Kaldor, New and Old wars: Organised Violence in a Global Era (Stanford, Ca.: Stanford University press, 1999); Stathis Kalyvas, ‘‘‘New’’ and ‘‘Old’’ Civil Wars: A Valid Distinction?’, World Politics, 54, 1 (October 2001), 99-100.

[xii] Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: A History of Violence and Humanity (London: Penguin edn., 2012).

[xiii] Peter Singer, Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century (New York: Penguin, 2009); Christopher Coker, Warrior Geeks: How Twenty-First Century Technology is Changing the Way We Fight and Think About War (New York: Colombia University Press, 2013), xix-xxv.

[xiv] Chris Hedges, War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning (New York, Public Affairs, 2002).

[xv] Michael Howard, The Invention of Peace and the Reinvention of War (London, 2000).

[xvi] Max Weber, Wirtschaft und Gesellschacht: Grundriss des vestehenden Soziologie (Tubingen: Mohr, 1972); John Locke, Second Treatise of Civil Government (London, 1690), ch. 7, section 87 and ch. 9, section 124. Francois-Marie Voltaire, Notebooks, (reprtd 1968), II, 547.

[xvii] Rob Johnson, Tim Sweijs and Martijn Kitzen, The Conduct of War, Op Cit.

[xviii] Azar Gat, War in Human Civilisation (Oxford, 2006); Quincy Wright, A Study of War (1942, reprntd University of Chicago Press, 1964).

[xix] Robert Johnson, Decision: Anglo-American Strategic Decision Making in the Two World Wars (Oxford, forthcoming).

[xx] Thierry Balzacq, Peter Dombrowski, Simon Reich, (eds), Comparative Grand Strategy, (Oxford, 2019).